“All great art looks like it was made this morning.” —Velvet Underground producer Norman Dolph

In 1995, two of the four Chili Peppers sat in a studio full of fans at the Canadian alternative music television network MuchMusic to promote their new album, One Hot Minute. To start what turned into a fun, sarcastic conversation, VJ Sook-Yin Lee asked Anthony Kiedis and Navarro how this project came together. “Well,” Navarro said slyly, “as you know, or may not know, I had completed a record with a band called Deconstruction, at which time I became a free agent. There was still some more solo work that needed to be done, some certain things I needed to get out, so I called up the Chili Peppers and said, ‘I’m working on this thing. You guys want to back me up a little bit?’ And they were into it.”

Kiedis studied Navarro’s poker face and played along: “This record, One Hot Minute, is really about Chad, Flea, and Anthony backing Dave up. It’s more of a solo project...”

“I was the catalyst,” Navarro said. “I allowed us to use the name Red Hot Chili Peppers just to, like, get it out there. You know, the kids are familiar with it. Put it out there.”

Their sarcasm was as dry as Death Valley, and watching it made me crack up out loud. Navarro’s hilarious, but the spirit of his opener was true: These kids in the audience probably hadn’t heard of Deconstruction.

As a Jane’s fan, I was saddened that Jane’s broke up after seeing them at the first Lollapalooza in 1991, but I was thrilled the members continued making music in Porno for Pyros and The Red Hot Chili Peppers. Navarro played incredible solos and imaginative melodies on the album One Hot Minute.

One Hot Minute sold well. It went gold in two months, eventually double platinum, spawned three hit singles, and reached number four on the Billboard Top 200 chart. That was successful by any standard, but because it sold half as many copies as the band’s previous album, Blood Sugar Sex Magik, it was treated as lackluster. But how could you compare anything to a smash hit?

“I’ve been asked, ‘How do you feel about making one of the least successful Chili Peppers records?’” Navarro said in Whores. “And my answer has always been, ‘Not only do I love that record, but it is, to this day, the most successful record that I’ve ever been a part of, commercial-wise.’ When I listen to that record, I hear myself growing as a musician and I couldn’t have had a better group of guys to learn from.”

One Hot Minute is the sound of opposing musical styles colliding and pushing the players into new, interesting directions, marking the album with enormous variety. In hindsight, it resembles a creative experiment in The Peppers’ funky catalogue and, whether a subset of Peppers fans like it or not, Navarro’s guitar style gave the band a sound they would never have again, which is, in a very real way, a musical success.

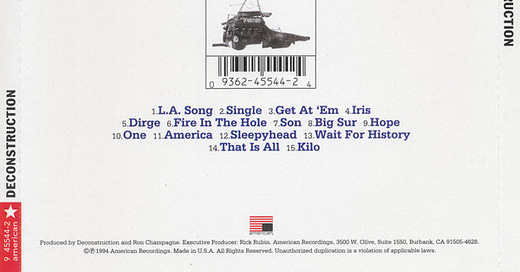

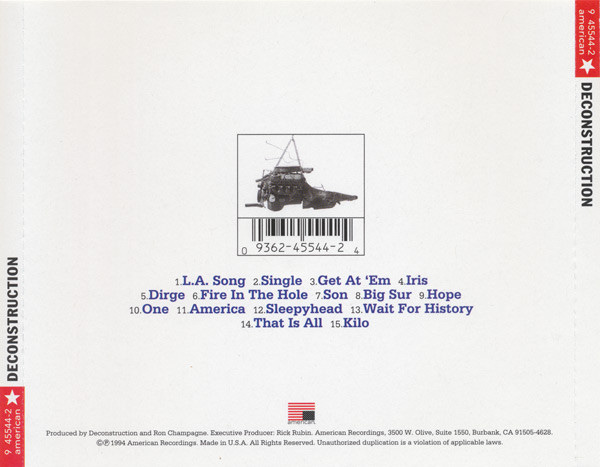

While The Peppers’ popular single “Aeroplane” circulated on MTV, Deconstruction’s “L.A. Song” video disappeared. But because Navarro treats his musical life is a progression, he took techniques from Deconstruction into One Hot Minute. Like the sound of Ronnie’s unborn son in “Iris,” a baby cries during a musical breakdown in The Peppers’ song “One Big Mob.” It’s Navarro’s 13-month-old baby brother, James Gabriel. “I recorded his voice on a Dictaphone,” Navarro told Guitar World. “I collect little sounds on tape, thinking they might serve some purpose later on. When that song came up in the studio, I didn’t know what to do with that section. It I played a real guitar solo, it would be really retro Seventies. Anthony doesn’t sing in that spot, and I was banging my head against the wall, trying to come up with something to put there. Then I realized, Wow, I have the perfect thing! I ran home and got that tape of my brother. It seemed to fit the mood perfectly.”

Navarro played in The Peppers for four years. In 1997, Jane’s Addiction reunited for their first tour since 1991. They called it The Relapse Tour. The name became literal.

“I had an amazing time,” Navarro said in Whores. “I have very little memory of it.”

Avery didn’t join, but Flea played bass in a way he hoped honored his friend Avery’s style and contributions. The beginning of the tour was powerful, but as the tour marched on, Flea watched drugs disrupt some of the energy. My friends and I saw them play that tour, and the energy was fully intact to us. But after the Jane’s tour, Navarro kept using, and in 1998, Flea called to say that the band had to let him go.

“If there was ever a time to part ways,” Navarro said in Whores, “that was the time. Flea had never seen that kind of chaos coming for me. I don’t think I was in a position to go back and I don’t think they were in a position to have me back.”

As much as The Peppers loved Navarro, they also didn’t gel musically. He could play anything, but unlike Kiedis and Flea, he was never a funk-based player. He was rooted in metal and gothic sounds, and it wasn’t natural for him to jam for hours with the band to generate music, and jamming, as Flea said, was the force of The Red Hot Chili Peppers. Naturally, their attempt to record a follow up album together fizzled.

When guitarist John Frusciante rejoined The Peppers, they quit performing One Hot Minute songs, creating a strange mystery around this phase in the band’s long life. When asked why they phased those songs out of their repertoire, drummer Chad Smith said: “We don’t really feel that connected to that record anymore. No special reason, not to say we’d never play those songs, but we don’t feel that emotionally connected to that music right now.” It’s a shame. They great songs.

In hindsight, Deconstruction resembled a mysterious gap in Navarro and Avery’s musical lives, too.

“Deconstruction, in a sense, went away all of the sudden,” said Avery, “instead of being the next thing that we were going to do. I don’t know if we thought that there would be multiple records out of it, but who knew? You were just doing the sort of next indicated step, and then suddenly the landscape was clear.”

While Avery formulated his next move, the so-called alternative music culture his band helped usher in continued to rage on. As the video for Jane’s hit “Been Caught Stealing” still circulated on MTV, the culture generators spit out new alternative band after new band. In 1994 alone, there was Live and Bush. There was Soul Coughing, Oasis, and Blur. Hole broke through with Live Through This as the world mourned Kurt Cobain’s death. Beck owned the airwaves with “Loser,” Green Day got huge, Smashing Pumpkins challenged its fans by evolving musically, and Rick Rubin poured his energy into relaunching Johnny Cash with his stripped-down American Recordings albums. Alternative music would remain a lucrative industry for a few more years, and Lollapalooza continued to bring it to American cities with its summer tour. Had the members been willing, Geiger and its other cofounders could easily have booked Deconstruction to play Lollapalooza’s second stage and brought them to that hungry youth market. Instead, from the view of us listeners, Navarro was all over TV, and Avery seemed to go underground—or as MTV put it, “basically fell off the face of the planet.” He was recalibrating, still exploring his identity as a musician.

In 1995, Avery met an English percussionist and engineer who taught him how to use a sampler, which led him to form the band Polar Bear with his friend Biff Sanders of the L.A. band Ethyl Meatplow.