Part 3: Four Epiphanies at Once

Making shit up as they go

In January 1993, the band started preproduction in a rehearsal space. Preproduction is the phase where a band polishes their songs to get them ready to record in the studio. Deconstruction refined most of their songs in preproduction, and Avery kept writing lyrics. “A lot of times we would record stuff, and Eric would go home, write the lyrics, and come back and put them in,” Navarro said, “so there were pieces of music that didn’t have finalized lyrical structure until we were in the room.”

“We really just came up with shit and were tinkering in the studio and then assumed we would go tour afterwards.” Avery remembers thinking: Let’s just approach the record, get it done, and then figure out how we’ll do it live later. “But at the same time, we were in a rehearsal studio, putting these ideas together,” he said, “always thinking of how to recreate it at the same time writing it at the same time trying to figure out if it was possible to do this.”

They needed a producer to make it possible.

“I got a phone call from my son’s mom,” producer Ronnie Champagne told me. “Alright, Dave’s on the phone. He wants to you to produce a record, and I’m thinking: Dave? I know three Dave’s: David Bowie, Dave Jerden, and Dave Navarro. Which one could it be? So I’m like, ‘Dave, yeah, okay. We don’t even have to talk about it. Let’s get down to business. Before I even say anything, I gotta hear what you guys are up to.’ I knew it’d be cool, obviously.”

Back in the music industry’s heyday, record labels often suggested producers to work on band’s albums, and bands came up with their own list of possibilities: How about him? How about her? Not every producer wanted to work with a band or could accommodate their timelines. Other producers pursued hot bands, only to recommend major changes to their sound, just to make hits. Sometimes the producer that the band wanted turned out to be the wrong fit. The Red Hot Chili Peppers were one of the hottest bands in Los Angeles in the early ’80s, but they always thought their demo sounded better than their self-titled debut album. That was partly because of the producer. “It became very much him against us,” singer Anthony Kiedis said in his memoir. But they loved what George Clinton did to their second album, Freaky Styley, as producer. And in the larger scheme of music history, Bowie’s masterful Low album would not have sounded the way it did were it not for co-producer Tony Visconti. And of course there was John Cale’s original rejected mix of the first Stooges album in 1969, and Bowie and Iggy’s warring mixes of Raw Power in 1971. There was a lot at stake.

A producer’s job is difficult, partly because the many duties they perform require very different skillsets. Producers book studio time and create schedules. Producers capture the feel of the studio room by finding the right places to place the right kinds of microphones. Producers manage personalities and interpersonal dynamics. Although some producers can be manipulative or domineering by imposing their taste and ambitions, the good ones encourage musicians to push themselves out of their comfort zone and try different things, from new guitar tones to singing in unfamiliar keys. And they ask difficult musical questions and tell bands things they don’t always want to hear, like telling Layne Staley to quit using heroin during the Dirt sessions and insisting someone other than Rick Springfield play guitar on Springfield’s hit “Jessie’s Girl.” They draft budgets. They arrive to the studio early and leave late at night. They manage recording technology and maybe manage the engineers and assistants. And they carry the pressure of delivering an expensive product on time, according to the budget, because their career, the band’s goals, and the label’s money are on the line. Most importantly, producers get bands to reimagine their own music, generating ideas, framing the album conceptually, refining song structures, to help make the songs the best versions they can be. When the studio set up didn’t capture the haunted, whispered feel that Kurt Cobain imagined for “Something in the Way” on Nevermind, producer Butch Vig quickly mic’d him on a couch and just let him play. That proved the best take.

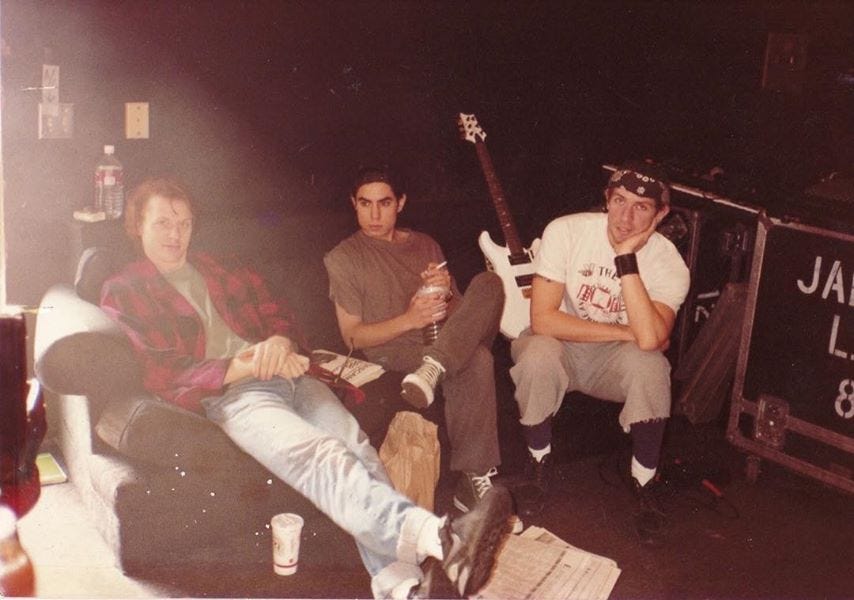

Ronnie had engineered Jane’s albums Ritual de lo Habitual and Nothing’s Shocking with his mentor, producer Dave Jerden, so he knew Avery and Navarro and had collaborated heavily with Navarro on his guitar sounds. “I don’t know if this was after the first tour or second Jane’s tour,” Ronnie said, “but Eric came up to me one day and goes ‘We had this thing going on onstage during soundchecks. Every time there was a problem, we’d all shout ‘Ronnie!’” With their history, chances were good that the 33-year-old would understand what Deconstruction was going for and get them there better than they could on their own.

Producing involves presenting possibilities without changing the band’s core character. Bands often hear themselves in the studio and think things sound good enough. A producer says, Yeah, it sounds good, but have you thought of this? Or how about this combined with that? “I’m the guy who goes: ‘Here’s how that could sound,’” Ronnie told me. “It’s so quick for me to go ‘This is what it could sound like, and let’s choose. Let’s see what works and then come to a consensus of yeah, that works best for the thing we’re working on.’” The creative aspect of music production involves presenting opportunities to build on what the band has and what they can’t yet hear.

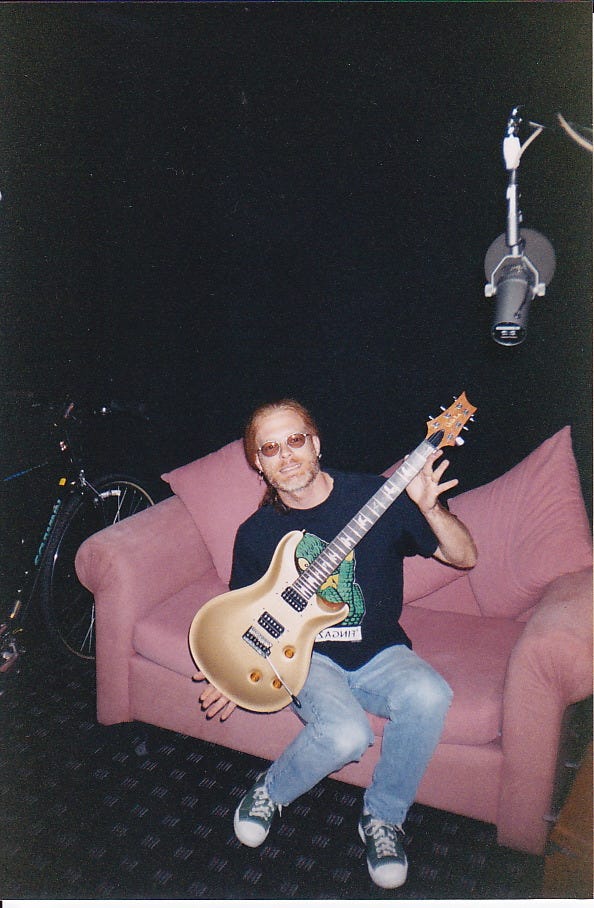

Currently living in Calgary, Canada, the 60-year-old Champagne still records, produces, mixes, and fixes albums by day, and plays live music at night. He wakes up at 5:30 each morning, does yoga, plays guitar for two hours, then gets to work. “If I don’t get up and do that, I can’t function,” he said. “I’m not a young guy, but the guys my age look like they’re fucking 20 years older. They’re completely unhealthy. They’d die of a heart attack in three seconds if they had to run because their house was on fire.” Time hasn’t changed his musical ideas. It only changed his equipment. Rather than working in studios as he used to, he now brings boxes of his gear to record at various locations, and he works remotely from home with digital files, surrounded by consoles, computers, keyboards, and endless equipment. “It’s easier now because look around: I got a fucking Gemini spaceship. You know what I mean? If I had all this shit back when I was making those other records, holy smoke, I probably would have taken twice as long because I had the possibilities.”

He’s always dealt with possibilities.