Part 1: The Hypnosis of the Drone

This is how you make art after your famous band breaks up

Eric Avery and Dave Navarro’s one-off, post-Jane’s Addiction side project started as a jam. When their band Jane’s Addiction had some time off, Avery and Navarro took a week-long trip to San Francisco in 1988, and they composed an instrumental sketch at a stranger’s house on borrowed equipment. “That was just an accident,” Avery told me 33 years after the fact. The bassist couldn’t remember the time of year or if Jane’s was between tours or between shows. He only remembered that he and Navarro were there together. They were always together. Back then, they were inseparable.

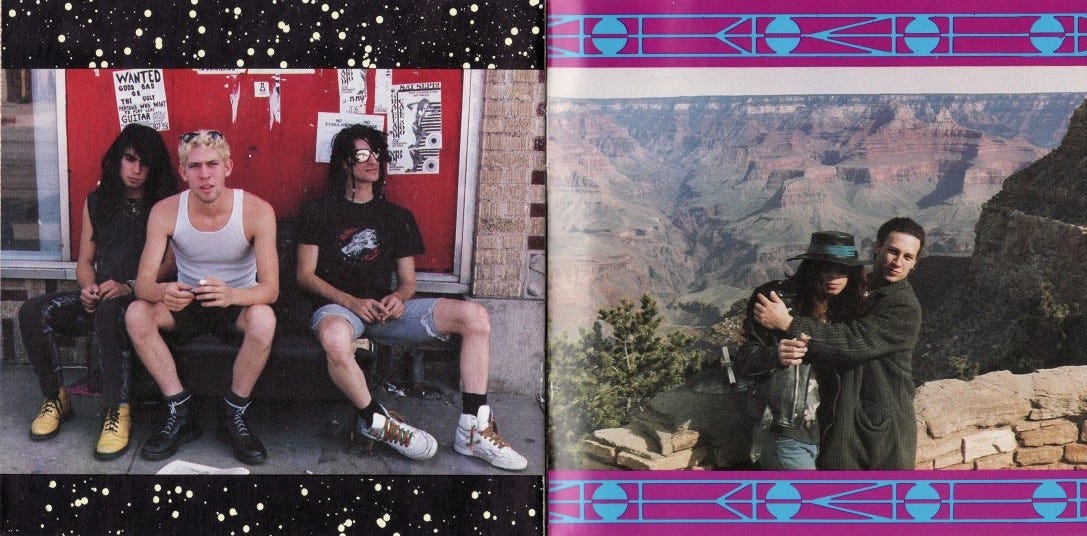

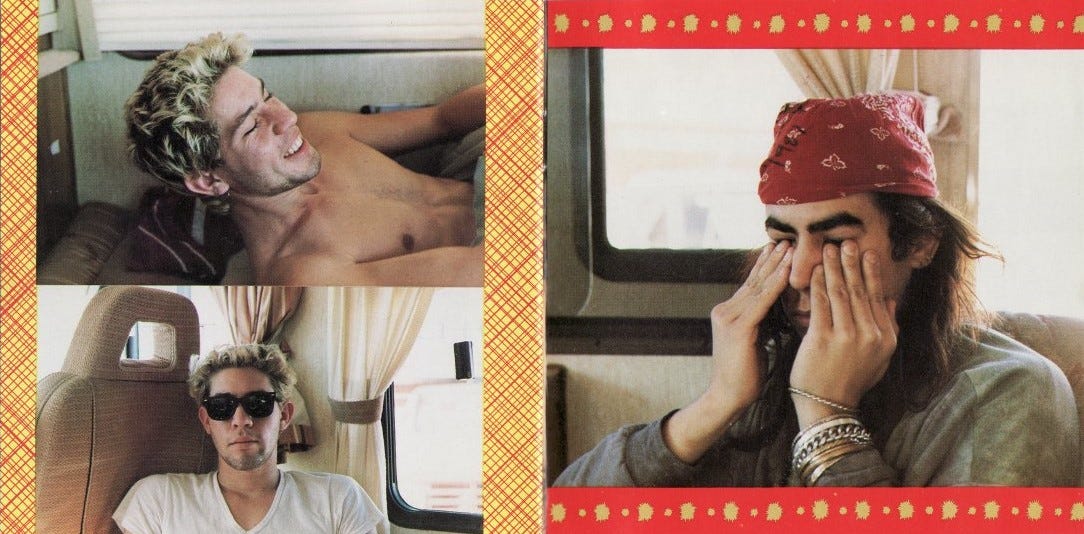

Jane’s Addiction toured for most of 1988. After releasing their independent debut record in 1987, Jane’s released their major label debut, Nothing’s Shocking, in 1988. But on tour, the band only graduated from a beat-up van to a beat-up Winnebago with a busted-out window, and they slept in cheap KOA campsites instead of costly hotels, crisscrossing the country and building a reputation as one of the country’s most explosive underground bands with one of rock’s most compelling lead singers. The time was a blur. The drugs blurred things further. “What were we doing up there? Heroin?” Avery laughed. “I think we were hangin’ out at somebody’s house who we didn’t really know—maybe a drug connection kind of thing. You know, the confabulatory nature of memory, I’m not certain about that. There’s a lot of San Francisco drug memories coming up in that neurological web that I’m not certain were all related to that [song].”

Navarro was certain. “I remember like it was yesterday,” the guitarist told me. “The origin story is that Eric and I were, again, loaded on heroin. We went to San Francisco. We were copping a lot of dope. We were walking around Haight-Ashbury, and we were kind of squatting with people we’d meet on the street and stay at their places—really just, like, an aimless trip. For no reason, we just went to San Francisco and fucked around for a week. So we met a couple of people that had a place on Haight. We stayed at their apartment for a couple of days. They had basses and guitars laying around. And one afternoon, I don’t know how or why, Eric and I picked up a bass and a guitar and just wrote that on the spot.” They didn’t plan on staying with strung out strangers. They didn’t plan anything. “It just wound up that way. They were like, ‘You guys could stay here.’ And we were like, ‘Cool.’ And we did.” The two left the city with a song and resumed life on the road.

Navarro and Avery named their sketch “San Francisco.” The music didn’t evoke anything particular about the city’s character. It evoked its conception. “I think it was just the trip, the time and how we felt being alive and free, roaming the streets,” Navarro said. “It’s still probably one of my favorite things Eric and I ever wrote.” The title was a placeholder. The song briefly became one, too, while Avery and Jane’s Addiction went through a profound transformation.

Avery, Navarro, and drummer Stephen Perkins sometimes jammed “San Francisco” as an instrumental during soundchecks at Jane’s shows. A fan recorded them playing it in October 1988 in Florida, where they were opening for Iggy Pop. Singer Perry Farrell was backstage. “He’ll be here shortly,” the band told the crowd before they ripped into this song then into “Up the Beach.” Another fan recorded them playing “San Francisco” at Hollywood’s John Anson Ford Theatre before one of a string of seven shows in April 1989, one of which got filmed, minus that song. When Perry ruined his voice and had to cancel a show in London in 1990, the trio even played “San Francisco” as part of a three-song instrumental apology set. The song also provided something to fill dead space if Perry’s mic went out during shows or when the crew needed time to fix malfunctioning equipment. “San Francisco” was fast, so it got peoples’ attention. It had one of those powerful cascading guitar riffs that put you in a trance the way “Up the Beach” did, except the guitar line was less aggressive, and Perry didn’t chant over it. Because soundcheck got everyone together in one place, soundcheck offered a convenient opportunity to flesh out this sketch. The band wrote most of their first two albums by jamming at rehearsal around Avery’s basslines. There was no reason to believe this wouldn’t become a Jane’s song, too.

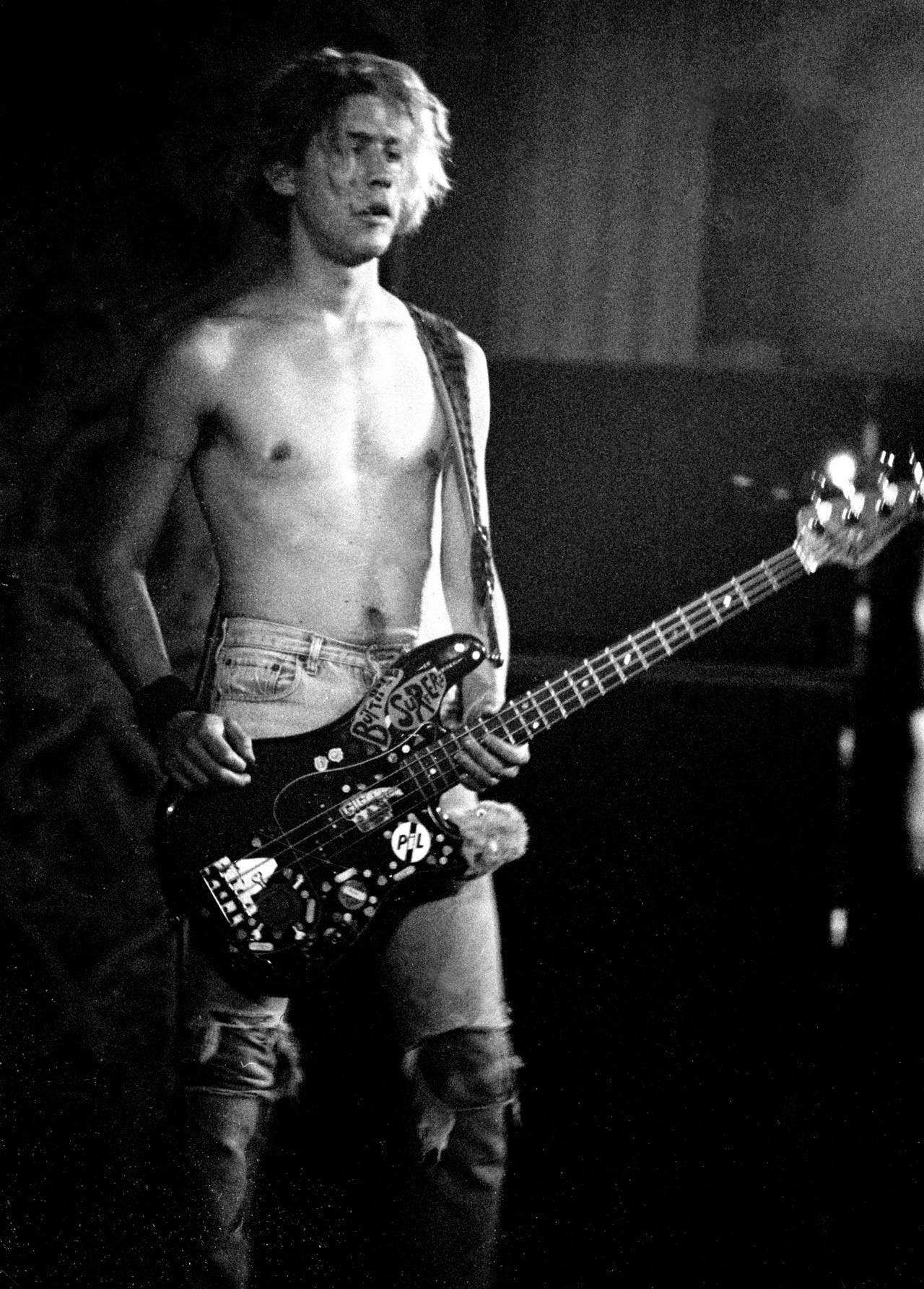

Avery had written a bunch of memorable basslines before he met Jane’s co-founder Perry Farrell in 1985, and the band quickly turned Avery’s grooves into some of Jane’s best songs, from “Whores” to “Idiots Rule” to “Mountain Song.” “The uniqueness of Eric’s bass and Perry’s voice together created the basic sound that is Jane’s Addiction,” said friend and singer Carla Bozulich. “[W]ithout Eric there never could have been any success for Jane’s Addiction.”

“Clearly Eric’s basslines were the signature sound,” Navarro said in the biography Whores. “His playing provided a whole dynamic that transcends words.”

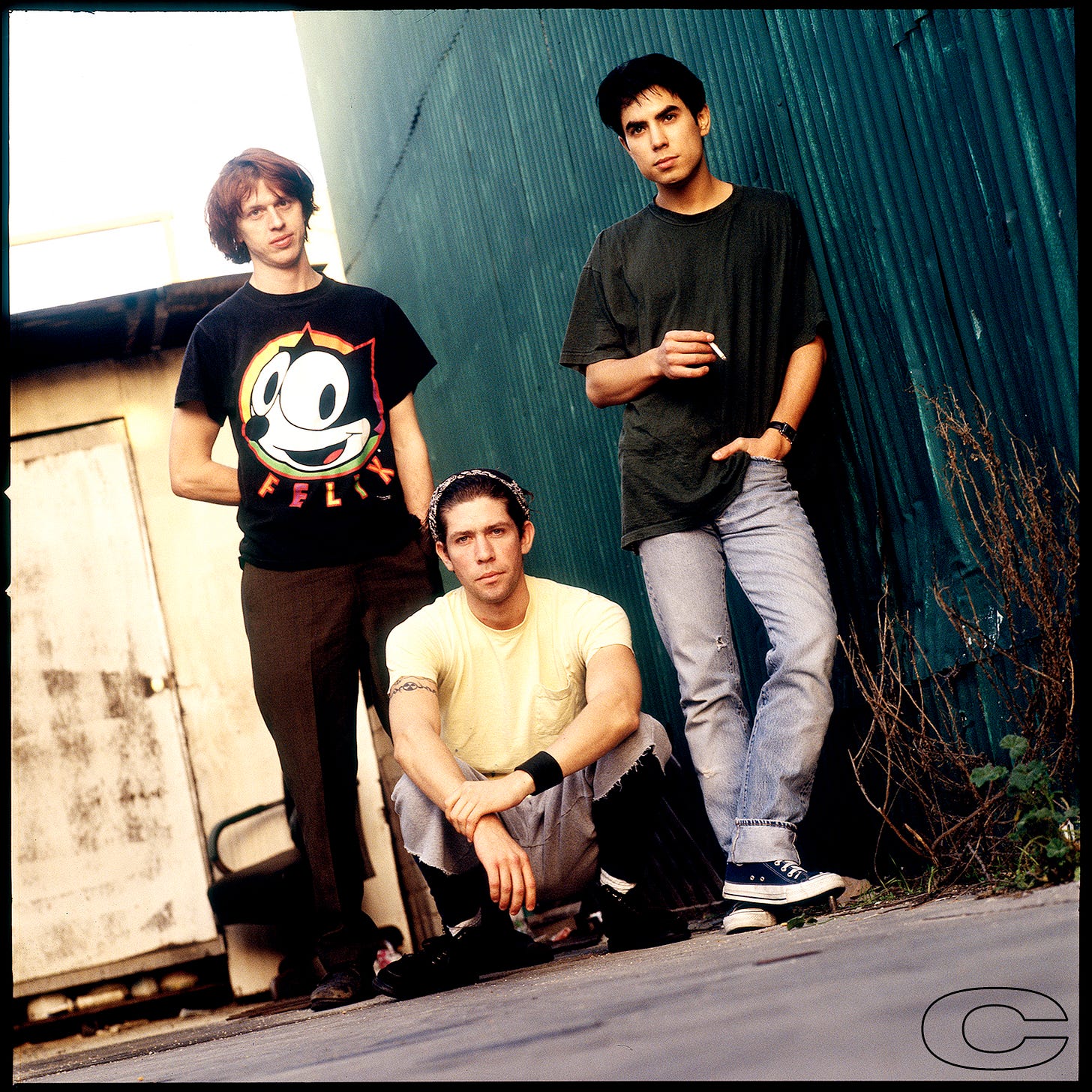

Many consider Avery the quiet genius behind Jane’s. Talented as Avery was, he could not have written these songs alone. “[N]one of them could have done what they did without the other,” said Bozulich. “At the time, I don’t think Eric could have come up with a melody line by himself that would have really worked, or a chord progression that would have fit [his bassline].” He needed collaborators. Jane’s songs were collaborations built around his cyclical, rolling basslines. Collaboration requires that band members get along. Jane’s did at first.

By 1990, the band was still touring for Nothing’s Shocking and were preparing to record their third album. They made good money performing, made great videos, and got enormously popular. If “San Francisco” was the direction their music was going, then the future sounded bright. But Jane’s still broke up in 1991, at the peak of their fame. Drugs, success, and conflicting personalities had poisoned members’ relationships. Tensions ran so high they could no longer compose as a group. They filled their third album, Ritual de lo Habitual, with songs they’d already written during better times and had perfected during years of playing. The members recorded most of their parts on Ritual separately, rather than in the same room. Jane’s barely managed to compose one new song for it, one that sounds unique in their discography, named “Of Course.” Perry wrote it, and studio engineer Ronnie Champagne played bass in Avery’s place, because Avery didn’t appreciate being told how to play his bass parts on that song or anywhere else. Only Perry and Perkins’ next band Porn for Pyros could flesh out the few old grooves Jane’s had laying around. One of Perkins’ drum rhythms, which they occasionally slipped inside “Pigs in Zen,” became “Blood Rag.” A Perry melody became “Packin’ .25,” and a fragment that Perry and Perkins jammed at soundcheck became “Bad Shit.” Nearly two years after Jane’s dissolved, “San Francisco” remained unrecorded. “San Francisco” was different.

“It was definitely the first thing that was ours,” Avery told me. “It was untainted by any concern about whether or not it was Perry’s idea first or more or less. It felt like ours. It was a little thing that was ours that we knew was great. And that might’ve been the genesis of both of us seeing the possibility of it.”